When Israeli activist Jeff Halper embarked on a

cross country tour of Canada recently, he spoke of a potential solution to the

Israel-Palestine conflict: the formation of a bi-national state like Canada, a bi-lingual,

bi-cultural partnership where everyone has equal rights as citizens, yet both

“nations” retain a

measure of self-determination.

Already there is a single de-facto government in the

region, Halper pointed out. Israel has created one state under its complete

authority, establishing a common currency, a single army, a single system for

the distribution of water and electricity, a single system of law. The region

is already bilingual; many Palestinians have learned Hebrew (often in Israeli

jails) and many Israelis understand Arabic. The problem is, it’s a highly

undemocratic arrangement, with Palestinians restricted at every turn, squeezed

into 38% of the occupied territories, which themselves comprise only 22% of

their original lands.

Already there is a single de-facto government in the

region, Halper pointed out. Israel has created one state under its complete

authority, establishing a common currency, a single army, a single system for

the distribution of water and electricity, a single system of law. The region

is already bilingual; many Palestinians have learned Hebrew (often in Israeli

jails) and many Israelis understand Arabic. The problem is, it’s a highly

undemocratic arrangement, with Palestinians restricted at every turn, squeezed

into 38% of the occupied territories, which themselves comprise only 22% of

their original lands.

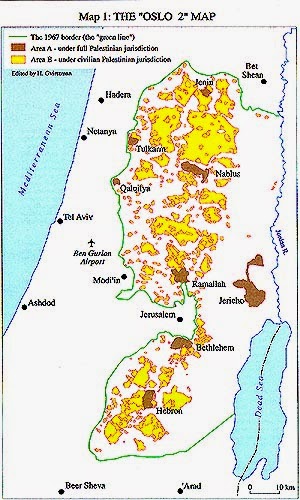

But what of the two-state solution, a compromise preferred by a majority of both Israelis and Palestinians and indeed, by Halper himself? The Israeli government has never seriously considered such an outcome, Halper says, and by now, the idea is no longer viable. With Palestinian lands now fragmented into more than 70 disconnected islands and dotted with more than 200 illegal settlements linked by 28 major highways, many barred to Palestinians, Israel has ensured that the West Bank is no longer detachable territory. By imposing a matrix of control and massive, permanent “facts on the ground,” Israel has divided the region so completely that even territorial swaps cannot create the contiguous geography necessary for two viable states.

So if there is already a single state, the task would be

simply to transform it into a true democracy. Everyone would have the right to

live, work, and travel where they choose. There would be no need for land swaps,

no demolition of homes, no policing of borders, and no fear of attack by the scary

people behind the “separation wall.” All barriers and checkpoints would be

removed, all confiscated lands returned, all segregated housing abolished.

Constraints

on Palestinian trade and commerce would be lifted. Water resources would be

equitably distributed, and with the help of international donations, damaged

infrastructure would be restored and improved. Children could go to school without fear.

With the binational state’s electoral

system open to all, the two peoples, so long separated from one another, would work

together to ensure that the rights of all are protected and each “nation” can maintain its own identity, its own sense of common history, its own customs,

languages, and religious practices within a geographic and civil structure that

ensures equality and celebrates the contributions of both groups.

With the binational state’s electoral

system open to all, the two peoples, so long separated from one another, would work

together to ensure that the rights of all are protected and each “nation” can maintain its own identity, its own sense of common history, its own customs,

languages, and religious practices within a geographic and civil structure that

ensures equality and celebrates the contributions of both groups. Idealistic? Certainly. Too complicated? No, such a radical transformation has been worked out before, notably in South Africa – though only after vigorous world pressure forced the government to shed its suffocating apartheid mode. Dangerous? Perhaps. Change is not without risk, especially for the occupying power. But this new vision, if entered into with good will and a sense of historical inevitability, could have the potential of creating a true democratic model for the Middle East, and indeed, for the world.

Here’s a link to Halper’s very engaging talk, which

mostly focusses on the demise of the two-state solution. Most interestingly,

Halper discusses who benefits from the permanent state of hostility, and warns

that the problems that beset the wider Middle East can only be solved after the

Israel Palestine issue is settled fairly and equitably.